Unresolved CFD-DEM#

Unresolved CFD-DEM is a technique with high potential for designing and analyzing multiphase flows involving particles and fluid. Some examples of these systems are fluidized beds, stirred-tanks, and flocculation processes. In this approach, we apply Newton’s second law of motion to each particle individually such that their movement is described at a micro-scale (as in DEM simulations). On the other hand, the fluid is represented at a meso-scale by a mesh of cells, to which we apply the Volume Average Navier-Stokes (VANS) equations.

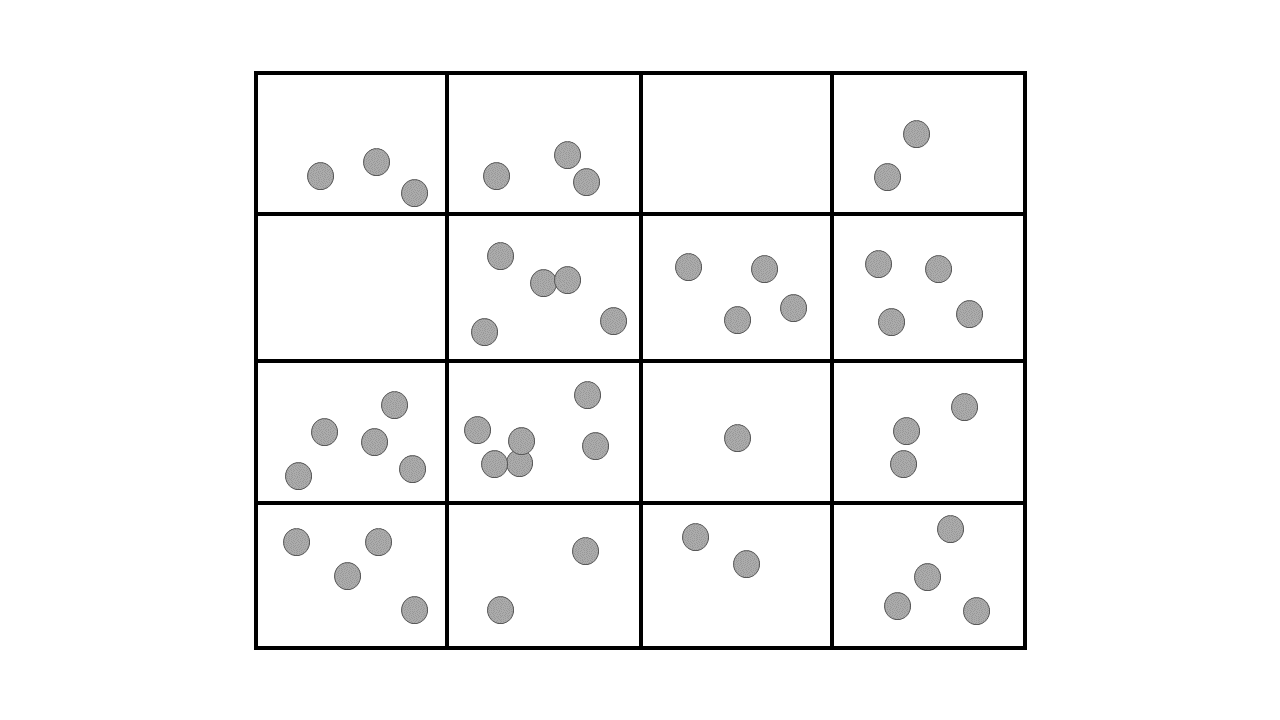

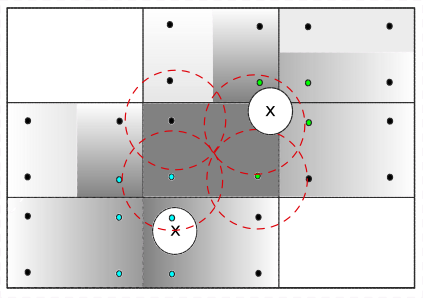

The micro-meso scale approach allows for particle-fluid simulations involving large numbers of particles with reasonable computational cost and highly detailed results (in both time and space). As a counterpart, the interchanged momentum between phases needs to be modeled, i.e., it is not obtained straightforwardly from the application of a no-slip boundary condition at the interface between the fluid and the particles. The following image represents the micro-meso scale approach applied in unresolved CFD-DEM simulations, where the rectangles represent mesh of the geometry and the gray spots represent the particles.

In this guide, we summarize the theory behind Unresolved CFD-DEM. For further details, we refer the reader to the articles by Bérard et al. [1], and Zhou et al. [2].

Particles#

Applying Newton’s second law and Euler’s law of angular motion on the particle \(i\) surrounded by fluid a \(f\), we find:

where:

\(m_i\) is the mass of the particle \(i\);

\(\mathbf{v}_i\) is the velocity of the particle \(i\);

\(\mathbf{F}_{\mathrm{fp},i}\) is the force exerted by the surrounding fluid over particle \(i\). Here, the subscript \(fp\) indicates the force exerted by the fluid on the particles;

\(\mathbf{F}_{\mathbf{g},i}\) is the gravitational force;

\(\mathbf{F}_{\mathrm{c},ij}\) are the contact forces (normal and tangential) between particles \(i\) and \(j\) (detailed in the DEM section of this guide);

\(\mathbf{F}_{\mathrm{nc},ij}\) are the non-contact forces between particles \(i\) and \(j\), such as cohesive and lubrication forces [4];

\(I_i\) is the moment of inertia;

\(\mathbf{\omega}_i\) is the angular velocity;

\(\mathbf{M}_{\mathrm{fp},i}\) is the torque exerted by the surrounding fluid over the particle \(i\).

\(\mathbf{M}_{\mathrm{c},ij}\) is the contact torque between particles \(i\) and \(j\). Since only spherical particles are currently supported the unresolved CFD-DEM implementation of Lethe, this torque is only due to tangential forces;

\(\mathbf{M}_{\mathrm{r},ij}\) is the rolling friction between particles \(i\) and \(j\);

The momentum transfer between phases, \(\mathbf{F}_{\mathrm{fp},i}\), can be written as:

where:

\(\mathbf{F}_{\nabla p,i}\) is the force due to the pressure gradient;

\(\mathbf{F}_{\nabla \cdot \tau,i}\) is the force due to the shear stress;

\(\mathbf{F}_{\mathrm{d},i}\) is the drag force;

\(\mathbf{F}_{\mathrm{Ar},i}\) is the buoyancy (Archimedes) force;

\(\mathbf{F}_{\mathrm{S},i}\) is the Saffman lift force;

\(\mathbf{F}_{\mathrm{M},i}\) is the Magnus lift force;

\(\mathbf{F}''_{i}\) are the remaining forces, including virtual mass, Basset which are currently not implemented in Lethe.

Note

Since the pressure in Lethe does not account for the hydrostatic pressure, i.e., the gravity term is not taken into account in the Navier-Stokes equations (see The Incompressible Navier-Stokes Equations), we explicitly insert \(\mathbf{f}_{Ar,i}\) in \(\mathbf{f}_{pf,i}\).

In unresolved CFD-DEM, the drag force is calculated using correlations (frequently called drag models). The drag models implemented in Lethe are described in the unresolved CFD-DEM parameters guide.

Void Fraction#

Determining the void fraction is an important step in unresolved CFD-DEM, as can be noted by the VANS equations and the drag models [5]. There exist several methods for the calculation of the void fraction in a CFD-DEM simulation. Some are approximations while others are analytical approaches. If one applies the averaging definition in equations (1) while taking \(b(\mathbf{x},t)=1\), one obtains:

This equation can be used in practice to calculate the void fraction at a given point \(\mathbf{x}\):

In the finite element method, the void fraction is initially calculated at quadrature points. However, the solution of the VANS equation requires not only the void fraction, but its gradient. Therefore, it is necessary to be able to represent the void fraction using a finite element interpolation (e.g. Lagrange Q elements). The best polynomial representation of the void fraction can be obtained by solving the following minimization problem (which is essentially an \(\mathcal{L}^2\) projection [7]):

where \(\epsilon_{f}\) is the void fraction, \(\varphi_j\) is the finite element shape function of the void fraction, and \(\varepsilon_{f,j}\) the nodal values of the projected void fraction. Then, we assemble and solve the following:

Lethe also has the option of smoothing the void fraction profile, which helps to mitigate sharp discontinuities. This is specifically advantageous when using void fraction schemes that are discontinuous in space and time such as the Particle Centroid Method (PCM) and the Satellite Point Method (SPM). To do so, we add to the left hand side of the previous equation a term similar to a Poisson equation. This acts as an additional parabolic (Gaussian) filter. The resulting equation is:

where \(L\) is the smoothing length, used as parameter in Lethe unresolved CFD-DEM simulations. In Lethe, three void fraction schemes are currently supported to calculate \(\epsilon_{f}\). They are the particle centroid method, the satellite point method, and the quadrature centered method.

The Particle Centroid Method#

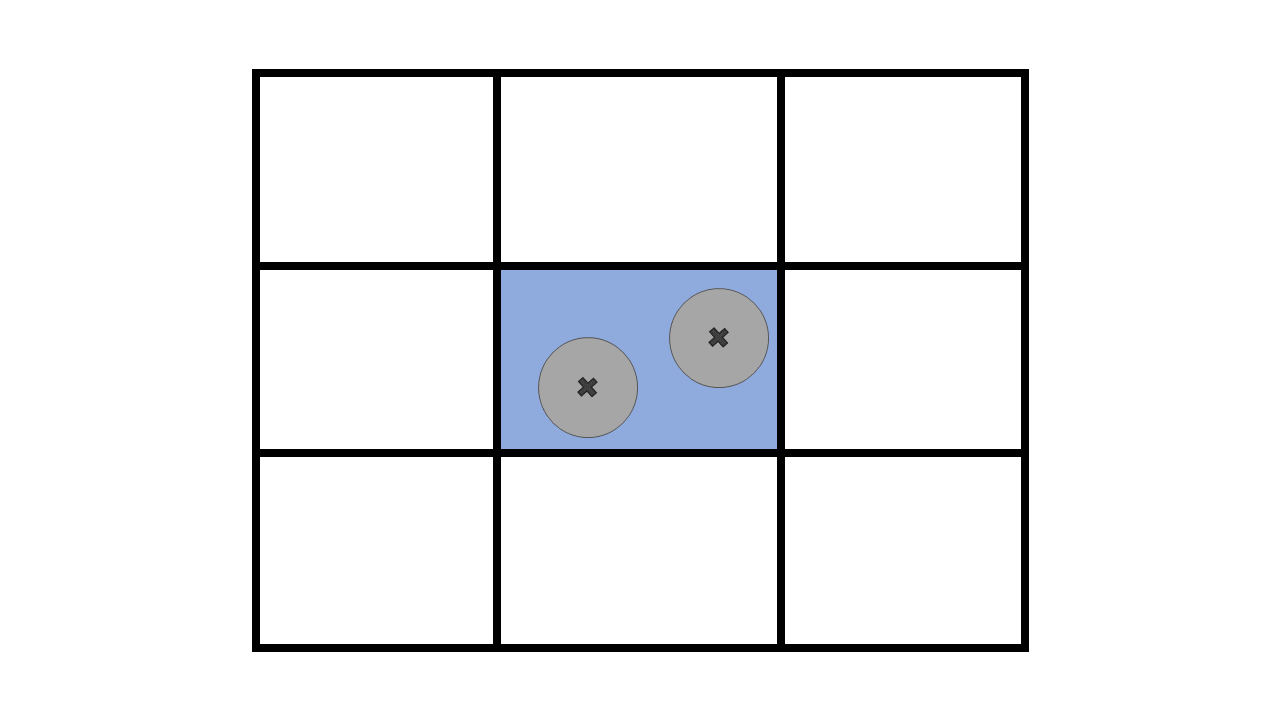

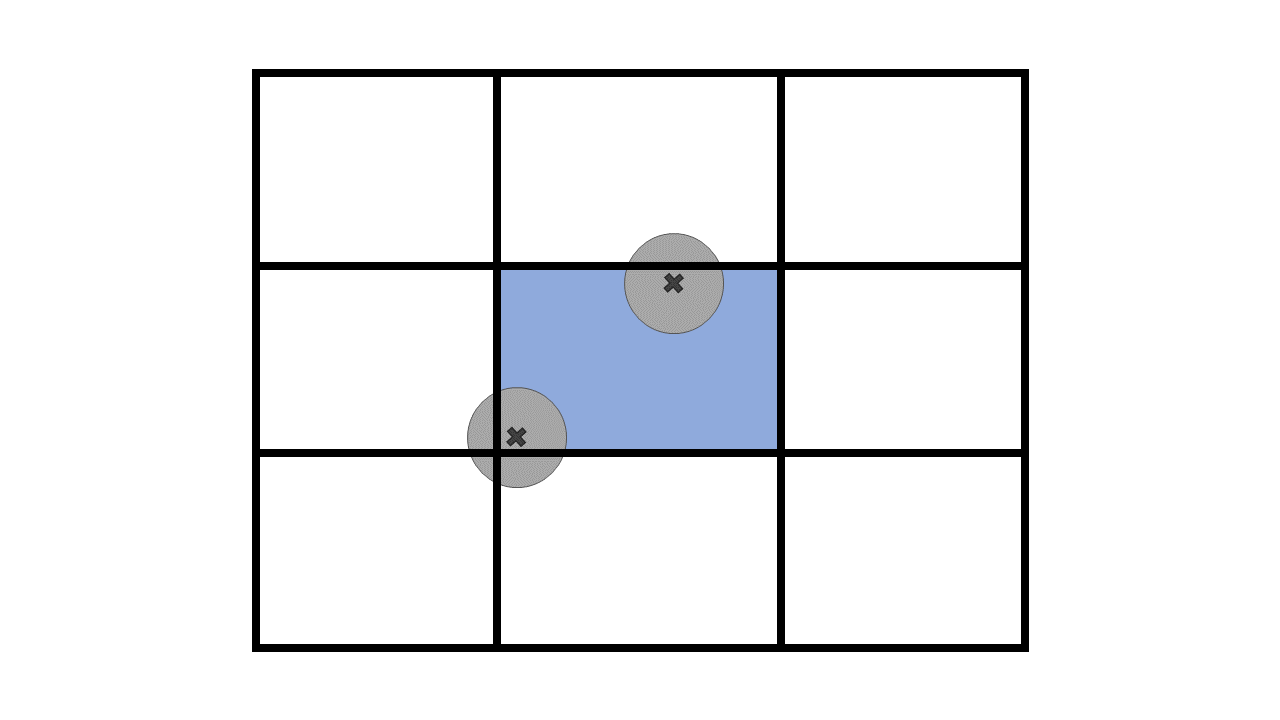

The PCM [6] is a simple and commonly used method. It consists of tracking the position of the centroid of each particle and applying the total volume of the particle to the calculation of the void fraction of the cell. This means that in either of the following situations the void fraction of the colored cell is the same:

This results in the PCM being discontinuous in space and time. Consequently, the PCM method significantly relies on the smoothing of the void fraction to lead to a sufficiently smooth void fraction field. We refer the reader to [8] for an extensive discussion on this topic.

The void fraction in a cell using PCM can be written as:

where \(n_\mathrm{p}\) is the number of particles whose centroids lie inside the cell \(\Omega_e\) of volume \(V_{\Omega_e}\). Comparing this equation with equation (2), we can see that this is equivalent to using the following weighting function:

where \(\mathbf{1}_{\{\mathbf{x}_i \in \Omega_e\}}\) is the indicator function that is equal to 1 if the centroid of particle \(i\) lies inside cell \(\Omega_e\) and 0 otherwise, and \(V_{\Omega_e}\) is the volume of cell \(\Omega_e\). It can be verified that using this weighting function for calculating the void fraction and the interaction forces ensures the conservation of mass of both phases, as well as Newton’s third law:

The Satellite Point Method#

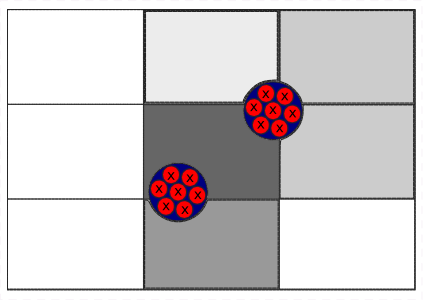

This method divides each particle into pseudo-particles where the sum of the volume of all pseudo-particles in a single particle is equal to the volume of the particle. Then, each pseudo-particle is treated similarly to the PCM, that is, the centroid of each pseudo-particle is tracked, and the entire volume of the pseudo-particle is considered in a given cell if its centroid lies within.

The void fraction in a cell using SPM can be written as:

where \(n_{\mathrm{sp}}\) is the number of pseudo-particles j belonging to particle i and with a centroid inside the cell \(\Omega_e\) with volume \(V_{\Omega_e}\), and \(V_{\mathrm{sp}}\) is the volume of the satellite point. The corresponding weighting function is thus:

This function is similar to the weighting function used in the Particle-in-Cell (PCM) method, but it varies gradually (albeit discontinuously) at the cell boundaries. Hence, it suffers from the same limitations as the PCM method. However, it also conserves mass. Lethe only supports the SPM for the calculation of the void fraction. For the calculation of the force with SPM, Lethe uses PCM.

The Quadrature Centered Method#

The Quadrature Centered Method (QCM) [8] is an analytical method that decouples the averaging volume from the mesh cells. It constructs an averaging sphere centered at each quadrature point in a given cell, and it calculates the void fraction directly in the averaging volume at the quadrature point. Since the sphere-sphere (particle-averaging sphere) intersection is analytically easier to calculate than sphere-polyhedron (particle-mesh cell), this method is less expensive than other analytical methods as the intersection does not involve the calculation of trigonometric functions at each CFD time step. The advantage of this method is that the void fraction varies within a cell. Additionally, particles in neighboring cells can affect the void fraction of the current cell. This allows the method to be continuous in both space and time. This is advantageous, especially in solid-liquid systems where the term \(\rho_f \frac{\partial \epsilon_f}{\partial t}\) of the continuity equation is very stiff and unstable, when there exist even small discontinuities in the void fraction, and where it explodes when \(\Delta t_{CFD} \to 0\).

An averaging volume sphere is constructed around each quadrature point. All particles lying in the sphere will contribute to the void fraction value of this quadrature point. Therefore, a cell will be affected by the particles lying in it and in its neighboring cells.

The void fraction at the quadrature point using QCM is:

where \(S_q\) is the sphere centered at \(\mathbf{x}_q\), \(V_{p\cap S_q}\) is the intersection volume of the particle with the sphere, \(w_q|J|\) is the weight at the quadrature point located at \(\mathbf{x}_q\), multiplied by the volume of the cell containing the quadrature point. The division by the product of the latter term and \(\sum_{q}{V_{\mathrm{p}\cap S_q}}\) is done to ensure mass conservation over the whole domain. The corresponding weighting function is:

This weighting function is also used to compute the fluid–particle momentum exchange term. Integrating this term over the computational domain demonstrates that the formulation also satisfies Newton’s third law (the corresponding expression is shown for Model B without loss of generality):

The averaging spheres must be sufficiently large to ensure that all particles in the domain contribute to the averaged void fraction, which can be achieved by selecting an adequate number of quadrature points together with an appropriate averaging radius, \(R_s\). However, in Lethe, the radius of the averaging spheres is currently constrained by the mesh resolution. Since each cell only has access to its direct neighboring cells, the averaging volume cannot extend beyond this local neighborhood. Consequently, the radius of the averaging spheres must satisfy:

where \(h_{\Omega}\) denotes the characteristic cell size. This limitation may be relaxed in future versions of Lethe.