Cahn-Hilliard Method#

The Cahn-Hilliard system of equations [1] is a model used to describe the process of phase separation based on the principle of free energy minimization. The key idea at the heart of the Cahn-Hilliard equation is that the system try to achieve a state where the free energy is minimized while competing with the energy cost associated with creating new interfaces between phases. Let us introduce those concepts formally.

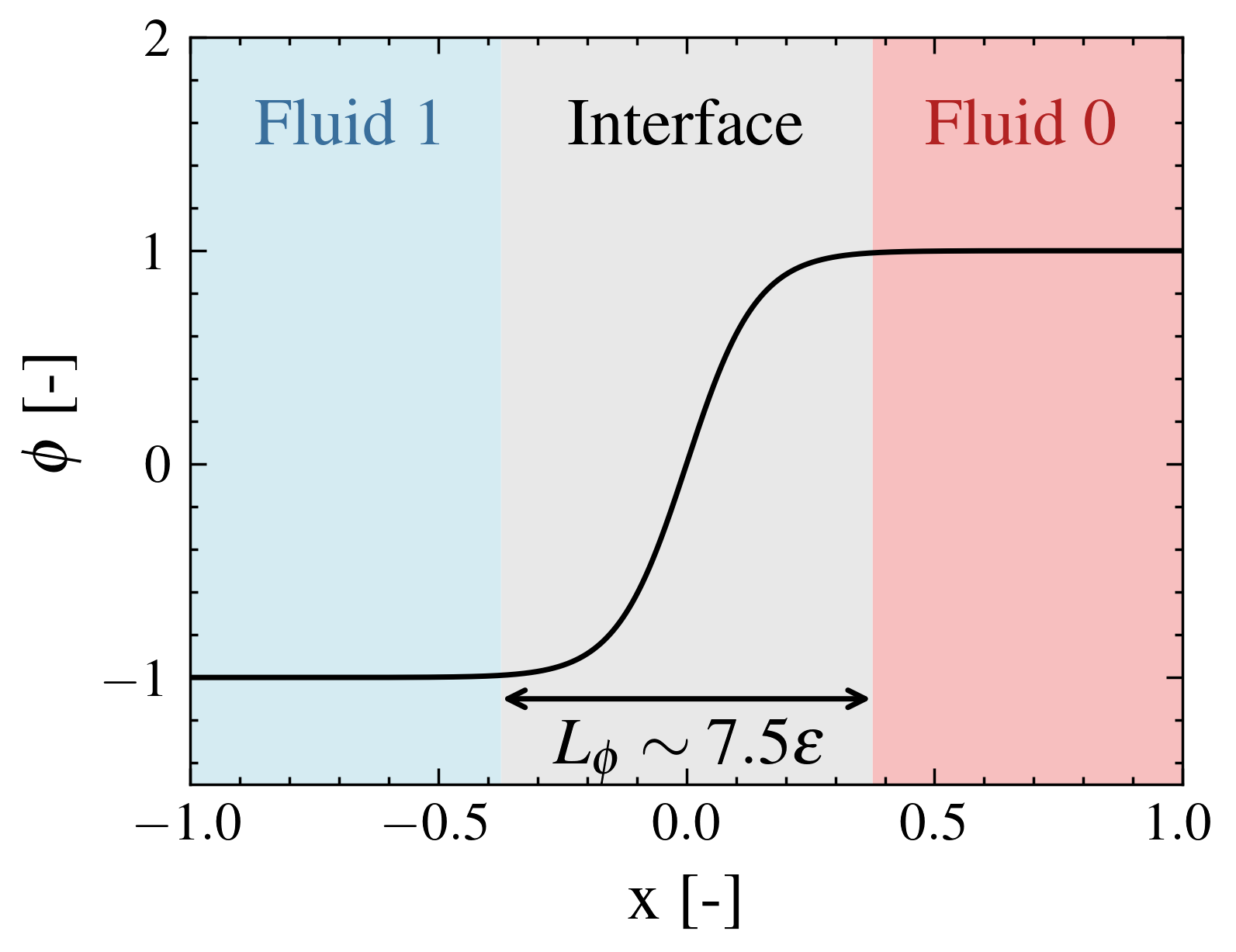

Let \(\Omega = \Omega_0 \cup \Omega_1\) be the domain formed by two fluids, namely fluid \(0\) and \(1\), with \(\Gamma\) the boundaries of the system. Like in The Volume of Fluid (VOF) Method, we define a scalar function \(\phi\) as a phase indicator such that:

The phase indicator transitions smoothly from one extremum to the other with the shape of an hyperbolic tangent function as illustrated below:

The length required to go from \(\phi=-0.99\) to \(\phi=0.99\) is about 7.5 times \(\varepsilon\), which we will see appear later in the equations.

Let us introduce the free energy functional \(\mathcal{F}\):

\(\Psi\) corresponds to the free energy density. Its expression is as follows:

It is decomposed in a bulk free energy \(F(\phi)\) and an interface energy \(\frac{1}{2}|\nabla \phi|^2\). \(\lambda\) is called the mixing energy though not dimensionally consistent to an energy. It can be understood as a scaling factor for the energy of the system and it is proportionnal to the surface tension coefficient. The bulk free energy has a double-well form, its expression is:

with \(\varepsilon\) a parameter related to the thickness of the interface between the phases.

To formalize the idea that the system tries to lower its free energy, we introduce a new variable, \(\eta\), called the chemical potential. It is defined as the variational derivative of \(\mathcal{F}\):

Then, the phases have to move to satisfy free energy minimization, by going from high chemical potential regions to low chemical potential regions. Let us introduce the flux of phase due to chemical potential differences, denoted by \(\mathbf{J}\):

With \(M(\phi)\) the mobility function. Then, we can write the following continuity equation, which also takes into account an external velocity field \(\mathbf{u}\):

To demonstrate that the stable solutions of the Cahn-Hilliard have naturally diffuse interfaces, let us look at a simplified 1D case in equilibrium: \(\eta = 0\) in the chemical potential equation. We obtain a differential equation on \(\phi\) whose solution is:

Lastly, we need to relate the surface tension coefficient with the mixing energy. Cahn and Hilliard define surface tension as the excess free energy of the system due to the interface, the second term in the expression of \(\Psi\). If we consider a system in equilibrium, and suppose a planar interface, we can write:

Substituting the solution previously found, we obtain the following expression for \(\lambda\):

For the problem to have a unique solution, we give the following no-flux boundary conditions on \(\partial \Omega\) for the phase field and chemical potential:

Finite Element Formulation#

Let us write the weak formulation. Let \(\alpha\) and \(\beta\) be the scalar test functions associated to \(\phi\) and \(\eta\). Let us first introduce the function spaces used to ensure the integrals exist:

We multiply each equation by their test function and integrate over \(\Omega\):

After using the integration by part and Green-Ostrogradski’s theorem:

Using Petrov-Galerkin method, the finite element formulation reads:

Find \((\phi^h,\eta^h) \in \psi^h\) such that:

Stabilization#

While developping the code, it turned useful to add a numerical diffusion term in the chemical potential form for some example. The new equation is:

With \(h\) the local cell size and \(\xi\) a user-defined smoothing coefficient (in general between 0 and 1). This fonctionnality may be deprecated later.

References#

[1] J. W. Cahn and J. E. Hilliard, ‘Free Energy of a Nonuniform System. I. Interfacial Free Energy’, The Journal of Chemical Physics, vol. 28, no. 2, pp. 258–267, Feb. 1958, doi: 10.1063/1.1744102.

[2] A. Lovrić, W. G. Dettmer, and D. Perić, ‘Low Order Finite Element Methods for the Navier-Stokes-Cahn-Hilliard Equations’. arXiv, Nov. 15, 2019. doi: 10.48550/arXiv.1911.06718.

[3] H. Abels, H. Garcke, and G. Grün, ‘Thermodynamically Consistent, Frame Indifferent Diffuse Interface Models for Incompressible Two-Phase Flows with Different Densities’. arXiv, Apr. 07, 2011. doi: 10.48550/arXiv.1104.1336.